Yemen is not starting from zero.

For over three millennia, Yemenis have engineered landscapes and water systems that remain among the most sophisticated in the world. Ancient Yemen faced unstable water availability and highly irregular rainfall, yet communities responded with resilience: thousands of stone dams, covered cisterns, terraces carved into mountains, and spate irrigation systems that turned floods into lifelines.

These ancestral systems were more than engineering feats. They included traditional rules for water distribution, conflict resolution, and community cooperation. Agricultural terraces slowed and absorbed floods, preventing erosion and recharging groundwater. Rainwater harvesting ponds and cisterns ensured year-round supply. Conservation farming practices recycled nutrients, protected soils, and secured food and fodder. Together, these regenerative practices sustained agriculture and communities for centuries.

Today, much of this knowledge has been eroded due to generational disconnect and reliance on imported technologies. Yet the opportunity is clear: blending new science with indigenous wisdom can transform heritage into a foundation for resilience, ensuring that Yemen’s future is as resourceful as its past.

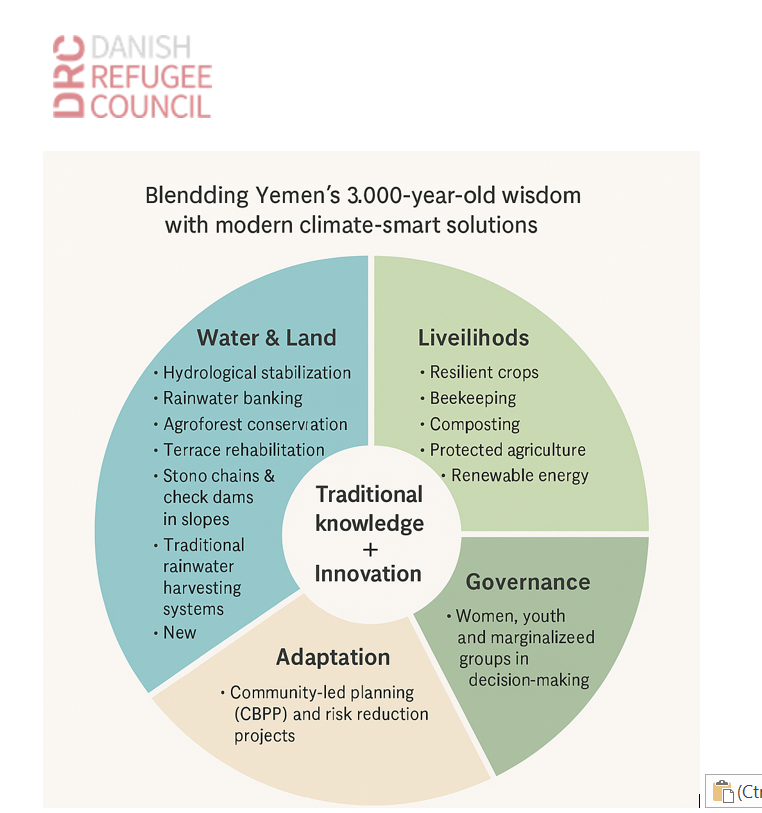

Danish Refugee Council (DRC) Yemen’s Regenerative Agriculture Design (RAD) framework blends this ancestral wisdom and ingenuity alongside modern climate-smart solutions. The RAD framework prioritizes water and land, livelihoods, adaptation, and governance—all centered on core traditional knowledge and innovation.

Learning from the Past: The Story of Wadi Bayt al-Ashwal

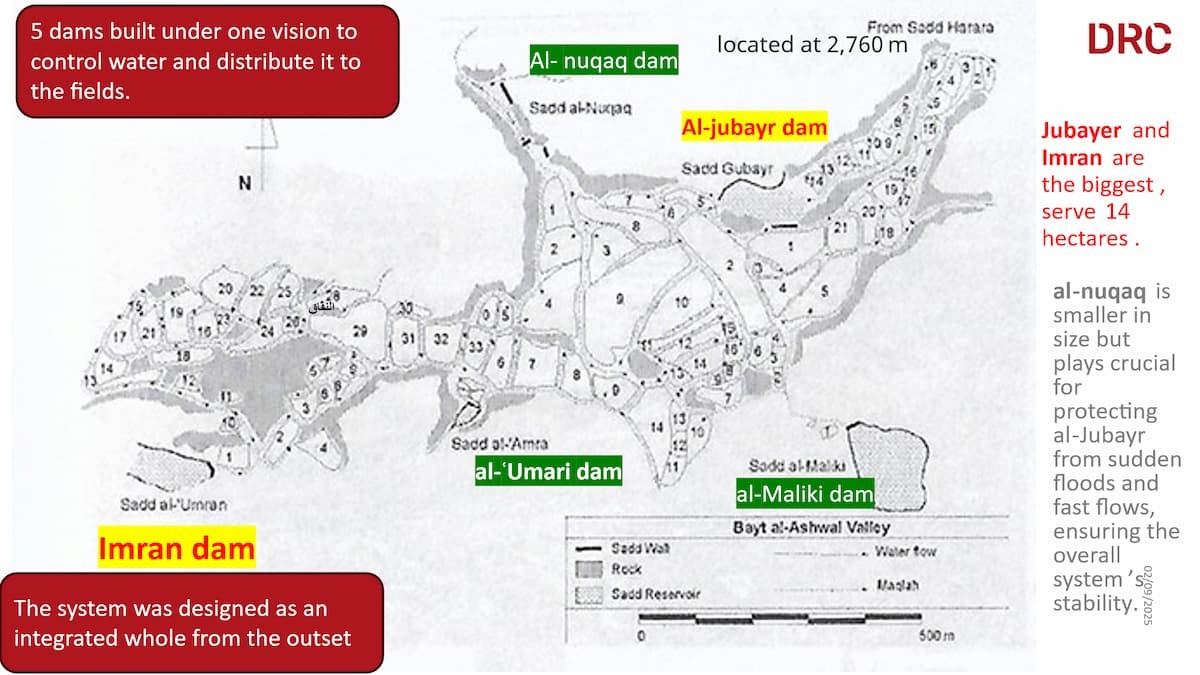

Centuries ago, in Wadi Bayt al-Ashwal, Ibb governorate, farmers engineered one of Yemen’s most remarkable hydrological stabilization systems. It was not a single dam or channel but a multi-layered package of dams, supporting arrangements, and cooperative irrigation practices that safeguarded communities for centuries.

1. Core Structures: The Five Dams

Bayt al-Ashwal is comprised of two main dams, two secondary dams, and a protective dam.

- Al-Jubayr (main dam): The heart of the system, diverts the largest share of floodwater into controlled irrigation flows.

- ‘Imran (main dam): Almost equal in size, serves as a “second lung” to ensure continuity and redundancy.

- Al-Maliki and Al-‘Umari (secondary dams): Smaller but strategically placed dams to irrigate side plots and extend coverage.

- Al-Naqqaq (protective dam): The smallest, yet vital, dam shields the main system by absorbing sudden torrents.

Together, these structures formed a water management hierarchy: storage, distribution, and protection working in harmony.

2. Supporting Hydraulic Arrangements

In addition to the five dams, farmers holistically designed the system to manage overflows and strategically slow, spread, and sink water throughout the landscape. The supporting arrangements include:

- Canals: Primary and branch networks distributing water.

- Spillways: Preventing overtopping and channeling excess flows.

- Swales (maqlah): Shallow ditches slowing floods, recharging groundwater, and reducing erosion.

- Field bunds (al-‘arim): Retaining water within plots to control irrigation depth and minimize runoff.

- Overflow outlets (al-mansah): Passing surplus water safely to the next field.

This skeleton of protective and distributive features turned dams into a controlled landscape system.

3. Cascade Irrigation and Social Cooperation

Fields were graded with gentle slopes, moving water by gravity in a plot-to-plot sequence. Once a field was filled, overflow entered the next plot. This design guaranteed:

- Equity: Limited storage capacity on the fields forced upstream farmers to release water.

- Recharge: Water infiltrated soils, replenished groundwater, and enriched fertility.

- Cooperation: Social agreements regulated timing and ensured fairness.

4. Integration as a Resilient Package

Viewed as a whole, Bayt al-Ashwal’s system was:

- Multi-layered: combining dams, canals, swales, and fields.

- Balanced: with protective and productive elements working together.

- Social-technical: sustained by rules and cooperation.

The thoughtful design has led to a resilient system that has endured centuries of floods, droughts, and pressures.

Linking Bayt al-Ashwal with DRC Yemen’s RAD Framework and Work

Bayt al-Ashwal demonstrates principles that align closely with DRC Yemen’s Resilient Agriculture Design (RAD) framework, which prioritizes:

- Assessment and Analysis: Careful reading of land, hydrology, and social needs shaped the ancient hydraulic system. Today, DRC mirrors this with tools like community-led planning, Participatory Capacity and Vulnerability Analysis (PVCA), and natural resource management (NRM) mapping. DRC uses these data to inform whole system designs of the areas in which it works.

- Design: Bayt al-Ashwal was conceived as a package, not piecemeal — a philosophy RAD applies today through watershed rehabilitation, check dams, rooftop cisterns, spate irrigation systems, climate-smart agriculture training, and inclusive governance.

- Monitoring and adjusting over time: The Bayt al-Ashwal system thrives to this day because farmers have observed, adjusted and adapted over time. RAD interventions follow the same principles.

These principles help build resilient systems: Bayt al-Ashwal absorbed shocks while sustaining irrigation—balancing safety and productivity—just as RAD interventions aim to do today.

Ancestral Practices Still in Use Today

Other ancestral practices reinforce the resilience of the system. DRC continues to draw from these, encouraging adaptation and applying modernized techniques, as needed.

- Terrace farming: Reduce runoff, recharged aquifers, and increase food and fodder.

- Rainwater cisterns (Qdhad plaster): Reduce costs, save time, lower groundwater pumping, and mitigate flood risks.

- Rangeland management: Rotational grazing to maintain vegetation and balance the ecology of the land.

- Post-harvest grazing: Recycle nutrients and improve soil fertility.

- Spate irrigation systems: Provide free, low-maintenance irrigation while recharging groundwater and reducing flood risks.

-

DRC is facilitating the rehabilitation of the Ras Al-Wadi spate irrigation system in Wadi Tuban, Lahj, Yemen. The restored structures improve flood diversion, protect farmland, and revitalize one of the country’s critical spate irrigation networks, securing water access for agriculture and community resilience. Credit: DRC Yemen

DRC is facilitating the rehabilitation of the Ras Al-Wadi spate irrigation system in Wadi Tuban, Lahj, Yemen. The restored structures improve flood diversion, protect farmland, and revitalize one of the country’s critical spate irrigation networks, securing water access for agriculture and community resilience. Credit: DRC Yemen -

Rehabilitation of traditional agricultural terraces in Asharaqi, Hajjah, Yemen, by DRC Yemen. These restored terraces stabilize slopes, reduce erosion, enhance rainwater retention, and revive indigenous farming systems that have sustained highland communities for generations. Credit: DRC Yemen

Rehabilitation of traditional agricultural terraces in Asharaqi, Hajjah, Yemen, by DRC Yemen. These restored terraces stabilize slopes, reduce erosion, enhance rainwater retention, and revive indigenous farming systems that have sustained highland communities for generations. Credit: DRC Yemen -

The Saqayn traditional water basin in Sa’adah, Yemen, rehabilitated with Qadhad materials. These plastered community ponds exemplify Yemen’s indigenous rainwater harvesting systems, which have provided reliable water storage for domestic and agricultural use for centuries. Credit: DRC Yemen

The Saqayn traditional water basin in Sa’adah, Yemen, rehabilitated with Qadhad materials. These plastered community ponds exemplify Yemen’s indigenous rainwater harvesting systems, which have provided reliable water storage for domestic and agricultural use for centuries. Credit: DRC Yemen

Lessons for Today

Wadi Bayt al-Ashwal proves that Yemeni farmers practiced resilience, analysis, and design long before modern frameworks. For DRC, drawing on this indigenous knowledge strengthens both training, implementation, and advocacy.

Regenerative approaches in Yemen are not foreign; they are a continuation of heritage—a bridge between ancestral ingenuity and today’s pursuit of climate resilience and food security.