Introduction

Before the emergence of modern early warning systems, local communities in Wadi Tuban, Lahj Governorate, relied on a combination of direct environmental observation and unwritten social agreements to predict floods and organize response measures. This knowledge was not mere habit; it evolved through generations of farmers, herders, and irrigation supervisors whose experience was shaped by daily life in a complex hydrological and topographical environment.

Local knowledge played a critical role in reducing flood losses and mortality rates, and became an essential component of water security and decentralized community-based governance. Yet, these practices persist today only modestly in rural areas, threatened by weak documentation, changing climate patterns, and a growing disconnect between younger generations and traditional environmental knowledge.

DRC’s Regenerative Agriculture Design

The Danish Refugee Council (DRC) prioritizes having a deep understanding of landscape rhythms, water flows, and community knowledge systems to inform its Regenerative Agriculture Design (RAD) work.

During DRC’s mission to Wadi Tuban in October 2025, farmers and irrigation-association members shared traditional early warning practices that remain active in parts of the valley. These practices offer practical intelligence on flood behavior, soil moisture, ecological signals, and water movement that is directly relevant to RAD, especially in flood-based irrigation systems.

The traditional observations documented in Tuban provide an ecological baseline that helps explain how communities have historically read the land, predicted hazards, and managed water distribution in a complex hydro-ecological environment.

This combined knowledge strengthens RAD’s core pillars: ecological literacy, watershed-scale planning, and community-led resilience.

Traditional early warning systems

Through discussions with farmers, elders, and local irrigation representatives, traditional early warning systems in Wadi Tuban can be summarized as follows:

1. Direct Environmental Observation

Careful observation of nature formed the cornerstone of local flood-warning practices.

These included environmental cues such as:

- Dark clouds over the Lahj–Taiz highlands signaled upstream rainfall and potential floods.

- Cool humid winds (Riyah al-Ghayl) indicated upstream rain, while hot dry winds from the Gulf of Aden signaled no flood.

- Animal behavior, such as goats climbing to higher ground, birds flying against the valley flow, and frogs suddenly going silent.

- A distinct “scent of wet soil” drifting from upstream warned of an approaching flood minutes to an hour before arrival.

2. Local Alert Systems (Rusal al-Sayl – “Flood Messengers”)

Communities organized upstream watchers to alert downstream settlements using horns, shouting warnings, and using fire signals on hills.

3. Seasonal Water Memory

Farmers used oral seasonal calendars to schedule canal cleaning, gate operation, and land preparation. Some mosques near the wadi still bear carved marks recording the highest flood levels from previous years, serving as a community water archive to guide construction safety and farming practices.

4. Water Infrastructure as a Safety Mechanism

Local communities showed remarkable ingenuity in adapting irrigation structures as protective systems. They built diversion weirs, temporary channels, and distribution gates.

This approach expanded the irrigated area and reduced destructive flood surges toward settlements in the lower valley, including the outskirts of Aden.

5. 'Uruf al-Sayl' – The Customary Flood Code

Upstream villages were obliged to notify downstream communities when major floods occurred, according to an unwritten social code called 'Uruf al-Sayl'.

This practice reflected deep community solidarity, as the safety of farmers and residents downstream depended on rapid alerts from upstream. It represents one of Yemen’s earliest organized forms of community-based early warning, long before the establishment of official monitoring stations.

6. Cultural and Knowledge Dimensions

Traditional knowledge became embedded in local literature and oral heritage, forming part of the region’s cultural identity.

Poet Ahmad Fadhl al-Qumandan captured this awareness in his verses:

“When the evening darkens and clouds gather; Ride to the valley and call aloud; Bring my cloak, the rain is near.”

These lines were not only poetic but also an observational call to prepare for rain and floods.

A local proverb conveys similar wisdom: “If lightning flashes from the north, climb higher, O farmer.”

Environmental observation thus evolved into a collective habit and cultural behavior passed down through generations.

7. Impact on Resource Management and Safety

Traditional systems enabled: early evacuation to save lives; asset protection by moving animals and equipment before floods; and improved irrigation efficiency by cleaning canals and readying gates for better water distribution, higher crop productivity, and reduced flooding in downstream urban zones.

8. Operational Lessons for Natural Resource Management in Wadi Tuban

These practices form a local operational system based on careful observation, community communication, and shared responsibility. They support participatory early warning, better irrigation management, and adaptive agricultural planning.

Strengthening RAD Programming

The traditional early warning systems practiced in Wadi Tuban are not mere remnants of ancient irrigation customs; they represent an integrated framework of environmental monitoring, social coordination, and shared responsibility, a frontline defense against sudden floods.

These practices have saved lives, safeguarded property, and enhanced irrigation effectiveness, building local resilience unmatched by advanced monitoring technologies.

DRC will use these insights to strengthen its RAD programming through:

- RAD Site Profiling: Environmental indicators are integrated into Tuban’s RAD ecological baseline.

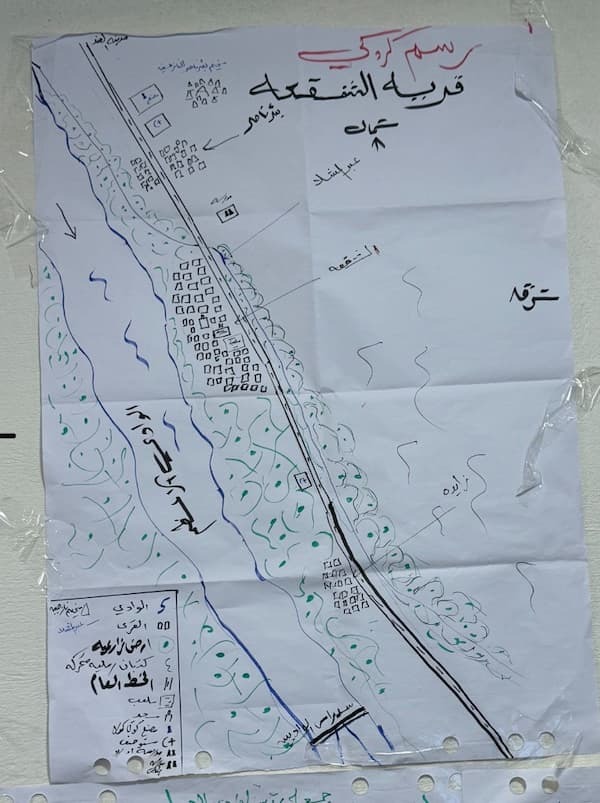

- Flood-Movement Mapping: Traditional signals refine hydrological modeling and guide regenerative structure placement.

- Canal and Gate Management: Oral flood calendars help plan maintenance and gate operations.

- Sequencing of Regenerative Activities: Flood timing guides when to prepare soils, plant fodder, establish trees, and stabilize soil structures.

- Community-Led Early Warning for RAD: Traditional systems like Rusal al-Sayl support community-based monitoring for RAD field sites.

- Integration into CSA and NRM: Traditional knowledge enriches water retention strategies, irrigation planning, and participatory watershed monitoring.

Conclusion

Studying the traditional early warning systems of Wadi Tuban is more than cultural preservation; it is a strategic step to strengthen community resilience, integrate local knowledge into climate-smart agriculture and natural resource management, and enhance adaptive capacity.

In light of increasing climate variability and urban expansion into flood-prone areas, documenting and integrating this knowledge into natural resource management, climate-smart agriculture, and local adaptation planning is essential.

To remain relevant today, this indigenous knowledge must be linked to formal systems, adapted to digital tools, and embedded within participatory community frameworks.

When combined, these efforts create a bridge between past and present, between human experience and modern science, forming a vital element in protecting rural livelihoods and building resilient communities in Wadi Tuban and across Yemen.